Domestic Violence Legislation Under Review After Police Officer Kills Former Girlfriend and Her Partner

Proposed Revisions to New Jersey’s Domestic Violence Act

The tragic acts of a New Jersey State Trooper have brought back into focus the domestic violence laws of the state. State Police Lt. Ricardo Jorge Santos allegedly shot and killed his former girlfriend, Lauren Semanchik, and her boyfriend, Tyler Webb, and then committed suicide. It has led lawmakers to rethink bills seeking to expand the domestic violence law of New Jersey.

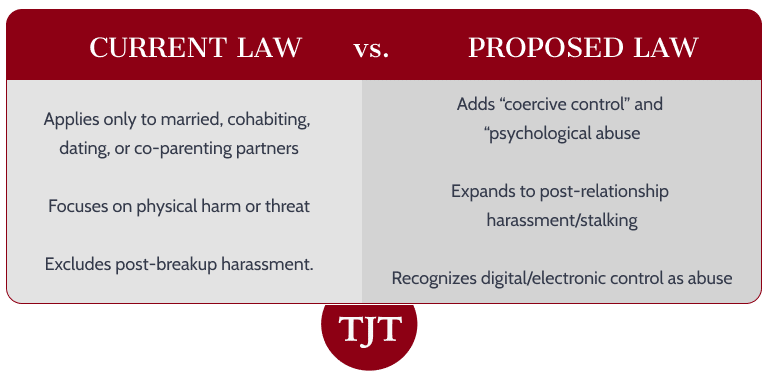

A bill, introduced in January 2024, would have expanded the definition of domestic violence under N.J.S.A. 2C:25-19. Current law limits domestic violence to certain relationships and significantly focuses on physical abuse or threat. Critics insist this disregards controlling behavior, stalking, and cyber harassment, which may be long-lasting even once a romantic relationship has ended.

Since the killings of Webb and Semanchik, the bill has gained steam among legislators. Supporters cite the case as evidence of the continued vulnerability of those leaving abuse, particularly because the legal system does not do more to stem non-physical coercion. Legislators are now seeking rapid action on the stalled bill. Lawmakers’ remarks within the next few months shall decide the bill’s future and any alterations to the manner in which the state approaches domestic abuse.

It is our firm’s mission to empower victims and fight for their rights. We help clients obtain restraining orders, push for their safety in the courtroom, and coordinate with police for prompt safety. During the time lawmakers are examining the domestic violence law of New Jersey, our cause remains: ensuring informed representation and fostering reform for each survivor’s ability to access legal protections.

Existing Legal Framework: Overview of N.J.S.A. 2C:25-19

N.J.S.A. 2C:25-19 delineates domestic violence within the Prevention of Domestic Violence Act of the State of New Jersey, applying to those married, living together, dating, or who are parents. They alone, by means of restraining orders, have the power to benefit from the Act. It employs a multifactor test to assess whether or not there is a “dating relationship” under the law, by looking to the length, nature, frequency of interaction, level of intimacy, and public classification of the relationship. Courts make these decisions on an ad hoc basis, often referencing evidence of oral hearsay or text messaging evidence to determine whether or not the bond meets legal thresholds. This subjective threshold is causing confusion, particularly where the relationships are short, long-distance, or internet-based. These definitional challenges are providing the impetus for new parliamentary action to reform the law and extend protections to victims beyond classical parameters.

Internet stalkers or post-separation harassment victims frequently feel insecure even years after the breakup. This occurs particularly with coercive controlling abuse, where the perpetrator, through the use of threats or manipulation, works towards dominating or alienating the sufferer, often not through physical means. Coercive controlling abuse is not yet categorized in state law.

Proposed Amendments to Address Current Deficiencies

Victims are put at a disadvantage by the existing law for post-relationship abuse, most significantly where the parties have not cohabited or have maintained the relationship briefly. Reforms would correct this by making harassment, stalking, e-surveillance, or intimidation grounds of protection upon the breakdown of the relationship.

Abuse such as continued unwanted contact, digital surveillance, threatening, or controlling surveillance would obviously be covered by the statute. Including post-breakup stalking/harassment, the bill shortens the distance between the end of relationships and legal protection from abuse.

It identifies an essential shift as the recognition of “coercive control” as domestic violence. Courts should consider behaviors that strip someone of liberty, integrity, or rights, including restricting access to money or healthcare, denying access to employment, and controlling movement, communication, or employment.

Post-Relationship Harassment and Stalking

The time immediately following the end of an intimate relationship is one of the most dangerous periods for victims of abuse. Studies from the National Institute of Justice and the CDC show that roughly three out of four domestic violence–related homicides occur after separation. This stage, often called separation assault, reflects an abuser’s loss of control and attempts to reassert dominance through intimidation, stalking, or violence. Victims who leave or begin rebuilding their lives—especially if they start a new relationship—frequently become targets of escalating threats. The murders of Lauren Semanchik and Tyler Webb highlight this pattern, where the act of leaving becomes the trigger for lethal violence.

Under N.J.S.A. 2C:12-10, stalking comprises a course of conduct that results in substantial emotional distress or fear for the safety of a reasonable person. It comprises repeatedly engaging in acts such as surveillance, communication, or threatened action. Although the law covers stalking broadly, it does not specifically take domestic violence into account. Establishing intent and patterns remains problematic where behaviors involve repeated texts, social media exchanges, or “coincidental” encounters. The prosecution may wait until an open threat occurs, and victims are left exposed in the earlier stages of harassment.

Crimes of stalking and civil restraining orders intersect but are not always concurrent. Restraining orders prohibit communication, possession of firearms, and maintaining distance. If a victim cannot document the existence of a “dating relationship,” they are left without the ability to have a restraining order and are subject to prosecution for stalking charges. This leaves the victim vulnerable to future injury.

Systemic Failures in Policing Domestic Violence Within Law Enforcement

Situations of police domestic abuse are of severe safety and systemic concern. Victims are exceptionally vulnerable because the abuser, by virtue of being the perpetrator, wields access to firearms, tactical training, and knowledge of law enforcement protocol. They may also have access to personal details of victims, including home and office addresses. Such access to power and expertise potentially renders the strategies of controlling them even harmful.

Victims are hindered from reporting officer abuse due to credibility issues and the threat of reprisals. The “blue wall of silence” (an unspoken code of silence among law enforcement personnel) may ignore witnesses, leaving victims alone. Despite documentation, agencies respond sluggishly, and victims risk denial or demands to abandon complaints to save the officer’s job.

New Jersey laws have included the mandatory surrender of guns clauses to prevent access by domestic violence abusers. However, making this stick with the police is not straightforward. Cops sometimes refuse to surrender, and their colleagues often overlook it, leaving holes of vulnerability. The refusal by police officers does not always come with the same punishment as that of civilians, and this leaves victims in danger.

It is the role of internal affairs to investigate police misconduct, but the procedures are always long and unclear. Investigations rarely come with harsh discipline, and criminal liability remains scarce for sophisticated abuses. That leaves us with a paradox: institutional protections for abusers detract from enforcement, and victims are abused once more within the protective apparatus.

Evidence Collection for Victim Safety

To prove abuse after a relationship, evidence must be gathered cautiously. Courts and police require evidence of harassment, stalking, threatening, or coercive action that results in a sense of fear or distress. Regularly keeping records of these occurrences strengthens the case for criminal charges and restraining orders.

Digital evidence features prominently in this century’s domestic violence matters. Texts, emails, social networking, and GPS tracking are capable of revealing patterns of unwanted contact. Perpetrator action and text evidence by metadata and screenshots are crucial. Security camera surveillance videos are also capable of substantiating accusations of harassment.

Witness statements can confirm the abuse pattern. Friends, neighbors, co-workers, or others who have witnessed the threat or the fearful response of the victim towards the abuser may come forward. Third-party reporting is indispensable for subtle, psychological, or hidden abuse.

Physical records are irreplaceable. Copies of police reports, 911 calls, and previous complaints build an official incident chronology. Records of injury or counseling can chronicle the cumulative effects of abuse. A concurrent record with a chronology of dates, situations, and the victim’s reactions is invaluable because it preserves chronic and coercive conduct.

Legal Accountability for Systemic Failures

System failures by the police suffered by victims of domestic abuse can cause injury or death and expose municipalities or police officials to civil suits. Victims of domestic abuse can bring a Section 1983 action under the federal civil rights laws, giving the power to bring suits for the violations of constitutional protections by officials of the government. Victims can bring the suits by asserting that the police officials showed deliberate indifference to known dangerous conditions by ignoring threats, failure to enforce restraining orders, or mishandling complaints of harassment. Courts decide if the police officials knew of key hazards and recklessly disregarded them, and this can be tricky but possible.

Abused victims and survivors of domestic abuse have the ability to file wrongful death actions or survival actions for damages. These suits highlight the manner in which the death could have been prevented by appropriate law enforcement action. Evidence such as complaints previously lodged, written threats, and officer consciousness is crucial to the imposition of liability.

Qualified immunity serves as the foremost hurdle to civil lawsuits against officers. Courts typically shield officers from liability unless it is demonstrated that they have breached known, clearly established rights. In domestic violence complaints concerning police, the plaintiffs have to establish the known risk under the current law. It is a burdensome process, but it can encourage more reforms.

Legal Protections and Community Resources for High-Risk Victims

It is crucial for survivors of harassers and stalkers to have plans in place to protect themselves. Effective strategies include technology, home, workplace, and legal methods of reducing risk, maintaining privacy, and forging protections while making life as normal as possible.

Technological safety matters. Victims should update passwords frequently, enable multifactor authentication, and use privacy settings. Devices should require password security or biometric locks, and victims must be alert to suspicious behaviors, such as tracking via apps. Avoiding shared calendars and geo-location sharing prevents offenders from accessing personal information.

Workplace safety consists of informing security or HR of risks, developing an emergency plan, and making adjustments to routines. Victims may be able to switch their transportation route, change their work schedule, or adjust phone and email access to restrict schedule awareness. Household safety, such as lock upgrades, placement of cameras, use of motion lights, and the inclusion of safe rooms, is also prudent. Regular check-in contacts are also very important. Legal protections span state lines. Victims can enforce restraining orders issued in one state under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) in other states, ensuring protection during relocation or travel. Multi-state restraining orders and awareness of interstate enforcement aid in preventing abusers from exploiting jurisdictional gaps.

Workplace safety consists of informing security or HR of risks, developing an emergency plan, and making adjustments to routines. Victims may be able to switch their transportation route, change their work schedule, or adjust phone and email access to restrict schedule awareness. Household safety, such as lock upgrades, placement of cameras, use of motion lights, and the inclusion of safe rooms, is also prudent. Regular check-in contacts are also very important. Legal protections span state lines. Victims can enforce restraining orders issued in one state under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) in other states, ensuring protection during relocation or travel. Multi-state restraining orders and awareness of interstate enforcement aid in preventing abusers from exploiting jurisdictional gaps.

Victims can access emergency relocation services, such as short-term shelter and financial assistance through NGOs or government initiatives. New Jersey’s Address Confidentiality Program enables victims to utilize an alternative address on public records to help hide from abusers. For comprehensive information on available support services, victims can review New Jersey domestic violence resources. This dual methodology provides victims with concrete self-protection mechanisms for resisting post-separation abuse.

Protect Your Safety and Secure Legal Protection from Domestic Violence and Post-Separation Abuse with Experienced New Jersey Attorneys

Our firm is dedicated to protecting victims of domestic violence and ensuring their safety within the framework of New Jersey law. We have extensive experience handling complex cases, including those involving law enforcement perpetrators and ongoing post-separation abuse, where victims face heightened risks and unique legal challenges.

We are full-service advocates, handling emergency temporary restraining order petitions through final restraining order hearings, appeals, and collateral civil matters. Our lawyers seek emergency protections and enforcement of current orders so victims have responsible legal representation where the matter becomes desperate. Timely access to the law could be essential to avoiding future harm.

Although we promote proactive law reform, expanding protections to survivors, active representation by the law as it stands remains our focus today to safeguard the well-being of our clients. The firm offers round-the-clock availability for domestic violence emergencies and provides free, confidential consultations. We help victims understand their options, develop safety plans, and take action without delay. Our commitment is to stand with survivors to protect their rights and their safety in both the short and long term.

As dedicated domestic violence and restraining order attorneys, we serve clients in Atlantic, Bergen, Burlington, Camden, Cape May, Cumberland, Essex, Gloucester, Hudson, Hunterdon, Mercer, Middlesex, Monmouth, Morris, Ocean, Passaic, Salem, Somerset, Sussex, Union, Warren County, and all across New Jersey. Contact us at (908) 336-5008 today for a free, confidential consultation.